First, if you enjoy reading about wines from culinary or terroir perspectives, I encourage you to consider upgrading to a paid subscription in order to assure access to all future posts. So let’s discuss…

Recently, in the hilltop medieval town of Sancerre, while discussing the different whites from among the surrounding villages with the owner of a restaurant, I was struck by the fact that the entire conversation was about the relation of soils and topography to the sensory qualities of the wine choices. The fact that all the wines might be iterations of Sauvignon was neither here nor there. When it comes to grapes, it seemed, you may as well be talking about the sun and the moon. It’s just there. The question of “great,” or even just “good” or “not-so-good” mattered even less.

Therein lies the enormous gulf between our cultures in Old World and New World countries in respect to how wines are defined. While a growing number of today’s American handcraft producers seem to want to change this algorithm, I would say that this gulf, at least in the commercial domestic market, is as big as it ever was. Even minimal intervention vintners are still hung up on concepts such as varietal character and personal brand. While Europeans still talk apples, we talk oranges.

“Is there great wine In California?” was the title of a landmark Esquire magazine article by Roy Andries de Groot, dated October 1, 1969. Its subtitle: “Is there balm in Gilead?” Given the date and circumstances, the question now seems akin to asking, while a baby is crawling across the floor, “Is this the next Michael Jordan, or Madonna?”

I’d like to share this article with you because, as the Stones once sang, it’s the singer not the song. I imagine every wine journalist starts off with role models. Rhetorical stance, after all, is everything, in order to come across with a sense of authority and, more importantly, integrity. Roy Andries de Groot’s prose exuded a particular rhetoric in spades.

In the mid-1970s legal drinking age was still 18, which was when I first started devouring all the wine books and magazines I could find. I still recall poring over de Groot’s 1969 article on “Great Wine In California” for the first time, sitting cross-legged on the floor between the tall stacks of collected periodicals, in the research library at University of Hawaii.

de Groot (1910-1983) was a British-born Baron who became better known as a culinary bon vivant. It is said that his senses became especially acute after he turned nearly completely blind, the result of eye injuries suffered during The Blitz of London. He emigrated to the U.S. in 1945, first working for the State Department, switching careers to food writing during the early ‘60s. These were the days when publishing in magazines such as Esquire, Ladies Home Journal, Playboy, Time, The New York Times, Gourmet or even House Beautiful and McCall’s was attached to significant prestige.

The Baron was also a prolific book author. In our house we still treasure his classic 1973 tome, Recipes from The Auberge of the Flowering Hearth, a highly detailed story of how de Groot once took an extended research trip to the Savoie in France to unravel the mysteries of Chartreuse. Since the Carthusian monks took vows of silence, de Groot did not get his story. Instead, he diligently transcribed all the seasonal dishes and wines prepared and served to him daily by two women who owned the Alpine inn where he stayed.

The days in Savoie stretched into weeks, then months, which culminated in de Groot’s “Flowering Hearth” oeuvre. We still read it for the inspiration and lessons of profound respect for the originality of regional cuisines and, eye-openly, an enormous range of wines of humble origins yet (according to de Groot) gloriously diverse taste—something I took to heart and applied throughout my career (28 years as a restaurant wine buyer plus two decades afterwards).

Don’t get me wrong. As much as de Groot readily extolled the magnificence of a Chiroubles Beaujolais cru, a Seyssel de Savoie Blanc de Blanc or Rosé d’Anjou—largely underappreciated wines, then as now—he also reveled in the magnitude of a Château Latour or Les Musigny by Domaine de Vogūe. Only, he could never think of a Latour apart from, say, Jeune Chevreau de Printemps au Morilles (young spring lamb stewed with wild mushrooms), or a Les Musigny without Tourte de Marcassin au Aubergines à la Crème (wild boar in pastry with creamed eggplant). For him, wine was never wine for wine’s sake. It always served an even bigger purpose.

I always knew, way back then, that it was strange for a sommelier to be influenced by what was essentially a cookbook c’est memoir, but I have always had a habit of reading between the lines to find a pervasive message. It has also been said that an untold number of chefs founded restaurants upon readings of “Flowering Hearth.” Find this book.

In his writings, de Groot appraised wines by key sensory components, the way chefs assess dishes by the way ingredients and techniques achieve a whole. We still consider de Groot’s recipe for Chicken Paprikas in his book Esquire’s Handbook for Hosts (1973) to be the ultimate version of this classic Hungarian dish; as much for its taste as its being an unfailing match with a good Pomerol or opulent California Merlot. In this book, extremely popular in its time, de Groot almost chortles through his chapters advising burgeoning gastronomes on finding a surer path to culinary sophistication, explicating details like the devil. What’s not to love?

By the 1980s, however, de Groot’s gastronomy influenced approach to wine journalism and evaluation came to be considered passé by the increasingly specialized wine media and industry dragged along with this navel gazing, despite the Baron’s long record of contributions. And originality. For one, finding UC Davis’ 20-point system too constricting when taking notes, he invented his own 50-point method that utilized the entire numerical range (unlike today’s 100-point systems in which, absurdly, almost all wines are rated strictly between 88 and 98 for obvious commercial purposes).

There was, however, no longer any use for any brand of wine journalism, or valuations, peered through the lens of quaint (or antiquated) concerns such as food, dishes, culinary culture or history. One of his last books, The Wines of California, the Pacific Northwest and New York (1982), was an ill-advised attempt to get readers to think of domestic wines in terms of place-defined classification systems of Europe. Although visionary, the still-fledgling industry was far from ready for anything of the sort, and de Groot was roundly criticized for being out of touch. Mainstream press can be cruel, like gangs of kids ruling the playground. Failing in health, de Groot died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound at his longtime home in New York City in 1993.

Hence, I often ponder, might this be my own fate? If not by gunshot, death by obsolescence? de Groot’s story now prepares me for, perhaps, an inevitability.

After all these years, wine, to me, still has little meaning outside the context of food. For me, wine without food is like rock and roll without the beat, or the need to dance. I think it’s silly to “rate” (or worse, worship) wines as things in themselves. It is also the conviction that even finest wines of the world should serve the primary purpose of being products of places, people and cultures—as far as I’m concerned, an inextricable relationship, the only one that matters. I shall die on this hill.

The following is the entirety of de Groot’s timeless contemplation recorded in Esquire on the state of California wine in 1969. Lest you forget, viewed through a European sensibility (in the late ‘60s American wines were still considered “naïve domestic” products of little “breeding,” at least in comparison to Old World classics). Much of de Groot’s pronunciations is outdated, parts of it speculative or in just plain error (like much of the wine journalism of those times). A surprising amount, though, is as meaningful as ever. I hope you read through all of it to absorb, as I still do, what the meaning and purpose of wine appreciation is all about.

That’s the moral arch of de Groot’s discourse. I find the details, particularly in historical contexts, to be fascinating. The article reminds you that the evolution of modern day California wine was a fraught and uneasy process. That the generations of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ’70 now considered conventional or old school by today’s standards were every bit as bold and daring as the “cool kid” winemakers of the present era. As de Groot notes, in most cases the production of the most significant wines of those times was minuscule, like drops in an ocean. Yet these were the wines that spawned the gigantic billion-dollar industry, and predominant consumer tastes, that we know today.

When we go to school we learn that we cannot understand the world without knowing its history. That, worse, we are condemned to repeat the mistakes and misperceptions of the past when we fail to heed those prior experiences.

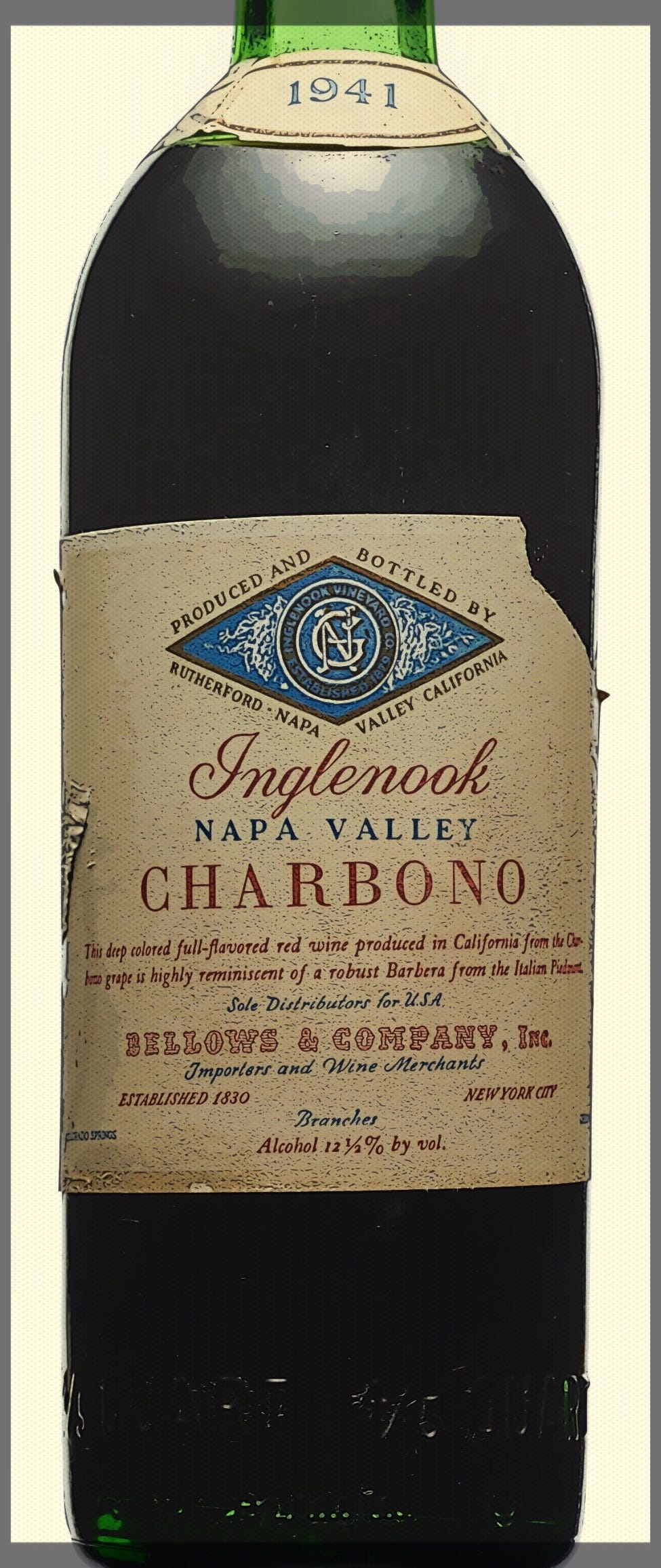

Above all, reading de Groot is a lesson in appreciating diversity and suppressing preconception. Something increasingly difficult to do in today’s world, ruled by so many hard and fast norms; that is, deference to seemingly beneficent status quo (something to which most of the wine world remains blissfully oblivious). Who else, for instance, could spend days in California hobnobbing with (now) legendary figures and powers that be, and come away with the conclusion that the finest California wine of all is a… 1941 Charbono! de Groot, thy name is Courage!

Read and learn from these timeless pearls of wisdom...

Is There Great Wine In California?

By Roy Andries de Groot, Esquire, October 1, 1969

The first and probably the worst wine ever made in California was born exactly two hundred years ago. In the Summer of 1769, the Franciscan friar, Padre Junípero Serra, rode north from Baja California on a large white horse, in company with the Spanish explorer de Portolá, into the newly colonized Spanish province of Alta California. The padre carried in his saddlebag cuttings of Spanish vines known as “mission grapes.” He planted them in the gardens of the newly dedicated Mission San Diego de Alcalá. When the vines bore fruit, the grape was described by a visiting English sea captain as “bluish-black, the size of a musket ball.” All contemporary reports agree that the wine was atrocious!

This vintage Summer of 1969 I rode into alta (or northern) California on a large white Boeing 727. I carried in my air bag a pad of wine rating charts and some large questions about the progress of two centuries, which, after all, is only a moment of time in the history of wine. Bordeaux has been in business for at least sixteen hundred years, Burgundy and the Rhineland for more than twelve hundred. The “Queen of French vineyards,” Château d’Yquem, has been growing the same strains of grapes for so many centuries that the earth, the air, the trees, the houses are all soaked with the natural bacteria and molds which the grapes need to ripen, ferment, and age to perfection. In California, the earth is still so “young to the vine” that laboratory-cultured bacteria and yeasts have to be added to the fermenting vats. You might say that California earth and air have not yet been sufficiently aged.

In fact, California’s wine industry is not two hundred but thirty-five years old. For the first hundred and fifty years there were but few individual growers planting wrong types of vines in wrong locations, producing large quantities of rough, adulterated wines and sweet dessert types of inferior quality. Then came Prohibition and the winemakers had to play dead for almost fourteen years. Repeal became effective on December 5, 1933, and that was the starting date—starting virtually from zero—of the modern California wine industry. On the basis of a little more than a quarter of a century, what I found last summer is in almost every way an extraordinary achievement. I found the expected immense flood of extremely cheap, relatively uninteresting gulping wines, plus a substantial supply of “good to superior” everyday table wines.

But my dramatic new discovery is that northern California now fully realizes that it has the potential (predicted by experts years ago) for producing “fine” wines, including a few “noble” wines and a very few “great” wines—to use the formal definition of the professional wine taster. You won’t find these top wines, of course, in local liquor stores across the country. Most of them never leave California; few get beyond San Francisco, where there seems to be an unlimited supply of thirsty connoisseurs. The rarest wines of all are bought at the vineyards and mostly consumed right in the valley where they are made.

During my tasting tour, I repeatedly asked why more of them cannot be made and distributed across the country. Different wine men gave me different answers. The problem, it seems, is in part economic, in part human and physical, in part because of the crazy patchwork of restrictive Federal and State laws left over from Prohibition and the temperance lobbies. The human and physical factors are dominant.

Year after year, California friends confirm my own opinion that the best U.S. white wine is made from the noble pinot chardonnay grape at Stony Hill—a minuscule vineyard of only thirty-five acres near the top of a steep hill overlooking the Napa Valley. When its owner, Fred McCrea, was a businessman in San Francisco, he and his wife in looking for a weekend place fell in love with the view from Stony Hill. They discovered that the pinot chardonnay grape throve on the dry and stony soil of the hill’s southern slope; the great grapes of the world make the best wine when they suffer a bit during growth. The McCreas built a cellar and installed a hand press.

After a few years of weekends, they decided that trying to make great wine was an irresistible challenge. They built a house and became full-time vintners. Through the summer, they are farmers, watching the developing grapes, deciding on the crucial moment when each bunch is at the perfect ripeness for picking. Three days too early and the wine may be too acid. Three days too late and the wine may be too soft. At the crushing in October, the McCreas are bacteriologists, when they add the yeasts to the fermenting vats. They are chemists, as they watch over the wine aging in the oak casks and choose the exact day, a year or more later, when it is to be bottled. Above all, they have to rely on their indefinable skills as tasters. The wine is ready after three years; usually about nine hundred cases.

They set aside as much as they need for their own use, then mail postcards to a list of San Francisco connoisseurs, pet wine shops and favorite restaurants. The message: “Have wine. Come and get it.” The cases are rationed. No one gets more than three. Some get only six bottles. The buyers gladly pay the price McCrea sets. Then the supply is gone and his commercial business is over for another year. Small wonder that the Stony Hill label is virtually unknown outside the Bay area.

Why doesn’t McCrea expand? If he had all the capital and skilled labor in the world, he couldn’t go faster than nature will allow. The noble wine grape is one of the world’s most finicky plants. It may make beautiful wine in one spot—mediocre wine in another a hundred yards away. To test each new location for planting would take him ten years—five before he could harvest the grapes and another five years before he could evaluate the wine. In making great wine, you can do nothing without time—decades of it.

How many of such dedicated vintners are there in California? And how large is their production? I began to find out on my first day in San Francisco, when I attended a “survey tasting” of thirty-five wines in the impressive cellar of the Russian Hill house of Harry Serlis, president of the Wine Institute of California. He stacks almost three thousand bottles, divided between Californian and European vintages.

For this and later tastings, I used a professional wine-rating chart which allocates scoring points to each of the special characteristics of each wine, including its aroma and bouquet, its taste, its acid, alcohol and sugar contents, its body texture, its degree of maturity. If a wine is terrible, it scores under ten points. A total score of ten to twenty-two means that the wine is of everyday quality—a good “gulping wine” to quench a summer thirst. A score of twenty-three to twenty-nine means an above-average, “good to superior” family table wine; thirty to thirty-five, a “fine” wine ; thirty-six to forty-two, a “noble” wine; forty-three or more, a “great” wine.

We started with a group of vintaged wines from the vineyards of Concannon and Cresta Blanca, with nonvintage from the Christian Brothers and Paul Masson. They all rated in the above-average class and showed how much wine making in California has improved, even in the last five years. Next, we opened bottles from the vineyards of Mayacamas, Mondavi, Sebastiani and Souverain, all in the “fine” class.

There followed an outstanding white, a “Limited Bottling” of a young pinot chardonnay, vintage 1967, from the venerable Charles Krug vineyard in the Napa Valley. It was spicy, delicately soft on the tongue, with a rich body, although it will obviously continue to improve with a few more years of aging. I rated it at thirty-six—safely in the “noble” class.

The climax of the tasting was a sequence of old bottles from the Napa Valley vineyard of Inglenook, generally considered to be the best in the U.S. for red wines. It was founded by an early California wine pioneer, the Finnish sea captain Gustave Niebaum. The bottles which we now began pouring were a gift from a member of that family, John Daniel, who took over after the captain’s death. (Inglenook is now a part of United Vintners.)

The youngest was a 1957 vintage of the noble red pinot noir grapes. Its twelve years of aging had given it an ample magnificence of taste and a delicate sweetness, while its body had amazingly retained a distant, fruity freshness. I rated it at thirty-six—also “noble.”

Next, to the vintage 1949, with a red from the cabernet sauvignon grape. Its twenty years of aging had magnified the aroma to an exquisite concentration, like the scent of an old cigar chest, while the taste was now superbly rich, with a gently noble sweetness, the body powerfully heavy. I rated it forty-one—the top of the “noble” classification.

The final bottle was sensational! In 1930, convinced that Prohibition was on its way out, John Daniel had brought to Inglenook some root cuttings of a relatively unknown Italian vine called charbono. It was a dangerous grape for northern California, since it matured very late and a single fall frost might ruin it. Nevertheless, John Daniel planted it. The Summer of 1941 was perfect for charbono. It ripened early, was picked in the middle of October and fermented fast and splendidly. The wine was aged in small oak casks for three-and-a-half years, then bottled. Twenty-five years later I was tasting the very last of these bottles.

The cork had been removed about two hours before. You could have heard a cockroach sneeze as the first glass was poured. A simple, black and white label read “1941 Estate Bottled” Inglenook charbono. The first flower of its bouquet was exquisite, the first taste superbly rich and warm, its sweetness noble, its body texture mouth-filling with power. It had surmounted its supreme test—it had not passed its peak. I rated it forty-four—a truly great wine—the best Californian I have ever tasted.

After such a spell of drinking some solid sustenance was indicated and I went to the Mandarin, one of the very few Chinese restaurants in town which maintains a good California cellar, to share a dish of “Smoked-Tea Duck” with Edmund Mirassou. He and his brother now run the family vineyard founded by their French grandfather in San Jose. Young Mirassou spoke of the “new surge” toward top quality, among even the larger growers. Previous generations of his family had concentrated on bulk production, but he and his brother are turning more toward bottling their vintaged single grape wines under their own label.

We drank his new 1967 “Limited Bottling” sauvignon blanc (the grape used in France for the white Graves of Bordeaux). This American version of the classic type had the characteristically delicate aroma, with a softly dry, yet racy taste. It rated a “fine” thirty-three.

This conversation raised the question as to how far the drive toward vintaged, single-grape wines had penetrated to the upper levels of mass marketing by the larger producers. So I spent the next couple of days talking to the presidents (and their production and marketing men) who influence, from their San Francisco offices, the drinking habits of millions of wine beginners. I found them to be charming, hospitable men, who sincerely seem to believe the extraordinary theories which they expound. They are against putting vintage years on labels. They argue that, in California, the unlimited sunshine makes every year the same. This thesis can be disproved in five minutes by a tasting of a few pairs of vintaged wines. There is more to the ripening of grapes than sunshine. There are the variations of average rainfall from year to year—the changing patterns of the morning and evening cooling breezes—the unpredictability of the fogs which roll in from the sea. .

The marketing men are frightened by vintage years. They fear that if the consumer starts worrying about whether 1968 was as good as 1967, there will be interruptions in the steady flow of computerized, mechanized sales. The marketing men think that the wines from the better years should all go into the same big pot with the poorer, so that what comes out is a consistent stream: The wine should be uniform in taste from year to year—uniformly bottled and labeled.

A refreshing exception to uniformity of the mass marketers is H. Peter Jurgens, the president of the huge Almadén Vineyards. He produced last year more than 1,800,000 cases and had a gross income of almost $17,000,000. He should, in the usual pattern, be thinking only of mass sales. On the contrary, his flexible, intelligent and restless mind has fully grasped the idea that the long-range future of the wine business lies in the direction of the high-quality, vintaged wines. He is convinced that the people who are buying the blended, mass wines today will soon get tired of uniformity and will begin to experience the excitement of the infinite variety of the fine wines. So he has planted five thousand acres of new vineyards entirely with noble grapes. He has set up what he calls “jewel cellars” in which to lay down and age his vintage wines. In a few years these cellars may be a substantial new source of fine California wines.

For the next few days I reveled in tasting wines with wine men at their vineyards. It’s almost a matter of pilgrimage to go first to Buena Vista, in the Sonoma Valley, one of the oldest and most beautiful estates. On a little knoll, with the view which gave the vineyard its name, surrounded by the noble cabernet sauvignon vines and the old stone cellars, I talked to the new general manager, Philip Gaspar and the winemaster who has run the cellar for sixteen years, Al Brett.

To spark the talk, Brett produced a cellar bottle of his vintage 1967 one hundred-percent single-grape gewürztraminer, the German grape which has been transplanted with some difficulty to California. Although this American version was lighter than its German or Alsatian counterpart, it had perfectly caught the gewürztraminer character: the exquisitely aromatic perfume, the spicy taste on the tip of the tongue, the faintly sweet softness in the throat. It rated a “fine” thirty-four.

I asked why more of such wines of strong character were not available for wider distribution.

These practical wine men (and others with whom I discussed the point) laid a large part of the blame on the inadequacy of U.S. wine-labeling laws. In every country the finest wines are those with the strongly individual character of a particular type of grape. Bordeaux is dominated by the cabernet sauvignon, Burgundy by the pinot noir. If you buy a French Chablis or Montrachet, the French government stands behind the label, to guarantee that the wine is made one hundred percent from the pinot chardonnay grape. There is a specific, legal label definition for every wine village in France. This is known as the “controlled appellation” law.

The U.S. has the weakest such law of any wine-producing country. If you buy a California bottle labeled “Pinot Chardonnay,” the law requires that only fifty-one percent of the wine in that bottle need be from the pinot chardonnay grape. The remaining forty-nine percent can be cheaper juice from any lesser grape. The unfair competition against the fine producer is obvious. He makes

his wine one hundred percent from the noble and expensive grape, and therefore has to charge, perhaps, $4 to $5 a bottle. His competitor, taking full advantage of the fifty-one percent law, is still allowed to mark his label pinot chardonnay, but can sell his bottle for around $2.25. Yet one has only to taste the two wines side by side to realize the one hundred percent single-grape is as a prince to the fifty-one percent pauper!

Wherever I went, I heard the fine producers describe the present law as “grossly misleading,” “dishonest,” “absolutely ridiculous.” They feel that the law must be amended to require that the wine be made one hundred percent from the grape named on the label, or that a lesser percentage must be clearly stated.

I returned to San Francisco for lunch, at the St. Francis Yacht Club, with Karl Wente, who now runs the family vineyards founded by his grandfather in the Livermore Valley. They are one of the largest of the northern fine-wine producers and have achieved national distribution for about 160,000 cases a year of their vintaged, single-grape, fine wines—but, of course, their best and rarest bottles are so few that they never even meet the local demand.

Our menu was splendidly planned by the club’s Swiss chef, Marc Proplan, to compliment the wines. I had asked Wente whether he thought that all California summers were the same and he answered by letting me taste, side by side, three of his pinot chardonnays. With a dish of Monterey Abalone Sauté Meunière, we had an old 1959, a 1966 and a cellar bottle of the 1967. The differences were striking! The oldest had developed an exquisitely mellow spice, almost entirely missing in the two younger ones. The oldest had a strength of taste, while the younger were merely delicate. The oldest was rich and heavy in texture, while the younger were simply in two shades of elegance. I rated the 1967 at an only “superior” twenty-seven, the 1966 at a “fine” thirty-two, and the 1959 at a “noble” thirty-eight.

Next, with Chateaubriand Bouquetière, Wente offered me a similar test between two of his red pinot noirs: a 1963 and a 1962. This time, age did not triumph. The bouquet of the older was much lighter; the taste of the older less dominant. In the 1962, the body power had not developed as it had in the 1963. The disadvantage of a poorer vintage year had not been overcome by extra aging. The 1963 rated a “noble” thirty-eight, and the 1962 only a “fine” thirty-five.

As we tasted, I asked Wente about the possibilities for the expansion of production of fine wines. He raised the question of the destructive threat hanging over most vintners of northern California—a blight more deadly than even the killing phylloxera vine disease. It is called “urban sprawl.” Marching up the Livermore Valley from overcrowded Oakland and Berkeley, the real-estate suburban developers have already wiped out at least a dozen small vineyards (just as the vineyards in Santa Clara and the Peninsula, around Los Gatos and San Jose have almost been extinguished). Some countries have laws protecting vineyards. In California, the tax law helps the urban sprawl. If a vineyard owner tries to hang on, even though he is surrounded by urban development, his taxes are raised, step by step, until his land is taxed as much as it would be if it were built over, and he eventually is forced to sell.

Wente and his vineyard neighbors (Concannon and Cresta Blanca) are fighting the urban sprawlers and there is a legal chance that they may yet be able to save the main beauty of the Livermore Valley. Meanwhile, as a security hedge, Wente is developing three hundred acres of irrigated vineyards in the Arroyo Seco Canyon, a hundred miles to the south, near Monterey. The good news from this narrow valley is that the white riesling grapes are producing test wines that are light, flowery and fruity, rather like that other narrow valley, the German Moselle.

Next day I went into the Napa Valley, which most connoisseurs consider to be the finest wine district in the U.S., our equivalent of the Burgundian valley of La Côte d’Or. I was invited to a meeting of the Napa Valley Wine Library Association in the old Hatchery Hall in the smalltown “wine-capital of the valley,” St. Helena. Here, once a week, this nonprofit wine-study society arranges for some of the Napa vintners to meet with a group of amateur aficionados to blind-taste and discuss a sequence of Napa wines from which the bottle labels have been removed. I found the members sitting at long trestle tables with spittoons on the floor beside them. There were visitors from Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco, an oenophile businessman from Chicago, a cluster of local drinkers.

The chairman of the meeting was the dean of Napa vintners, Louis M. Martini, who runs the family vineyards founded by his father. Through a passionate devotion to excellence, father and son have achieved national distribution in excess of 209,000 cases per year of their vintage, single-grape, fine wines, but, as always, the “best bottles” are so few that they never travel far from home. I had called Martini earlier in the day to ask if I might taste some of his rarest, most historic, most-in-demand, hardest-to-get wines. He said, “I’ll have to go to the cellar—I’m the only one who knows where they’re hidden.”

The first was a light red zinfandel, the “mystery grape” of California, which grows nowhere else in the world. Viticultural botanists are sure that it was imported originally from Europe and have been trying for thirty years to trace its ancestry, without success. When its wine is young, it is a nice, fresh, relatively undistinguished thirst quencher, but Martini has proved, perhaps better than any other vintner, that when the zinfandel wine is made originally with a light tannin content and aged up to twenty years it develops magnificently. This example was a 1947 “Private Reserve.” Its aroma was exquisitely spicy, its first taste showed great character, it had achieved with old age a superb softness, yet its body texture had remained juicy and it was still, after twenty-two years, at its peak of maturity. It rated a “noble” forty-one.

Next, a venerable 1947 “Private Reserve” cabernet sauvignon, with an exquisitely complex bouquet, a first taste of great fullness and warmth, with a vivid range of flavors, a noble softness and a body texture of magnificent power. It rated a “great” forty-three.

The third was an astounding wine, a white 1962 semillon from a year when there was more than ten inches of rain in the middle of the harvest and the grapes were finally covered by the “noble mold,” the botrytis cinerea, which, in France, produces the great natural sweet wines of Sauternes, but which almost never affects the grapes in California. So this semillon, normally a dry wine, was, by an accident of nature, delicately, marvelously sweet and rated a “noble” thirty-six.

As we tasted, I again asked why I had to come to California to find such wines. Then several of the growers raised another thorny legal problem which is holding up the progress of the fine-wine producers: California’s so-called “Estate Bottled” ruling.

Many years ago, it was decided that this phrase, printed on a California wine label, should be the equivalent of the French “Château Bottled” standard. In California a wine labeled as “Estate Bottled,” must be made one hundred percent from grapes grown on land immediately surrounding the production buildings. There is no definition as to the quality of the grapes—no guarantee that the wine is one hundred percent from a single-grape variety—as in France. It was intended that the “Estate Bottled” label should be a mark of the highest quality. It has not worked out in practice. Martini and other fine wine producers, as they have expanded, searching for the best plots on which to grow the noble grapes, have not always been able to find good land “immediately surrounding” (or “adjacent to” in the legal language) their own original vineyards. For example, Martini brings his zinfandel grapes from the Sonoma Valley, where they grow better than in Napa. But the moment a vintner gets his grapes from another place, even a hundred yards down the road, he may no longer use the “Estate Bottled” label.

On the other hand, some of the mass-producers of inexpensive everyday wines have huge tracts of land planted with relatively inferior vines. They have never shouldered the expense and trouble of replanting their vineyards with the noble grapes. Yet, by a quickly-out-of-date State ruling, they may label their mediocre wines “Estate Bottled.” Many of the smaller producers regard this as unfair competition and misleading to the public. They feel that the chaotic and meaningless “Estate Bottled” rule should be amended or repealed.

Meanwhile, Wente has abandoned the “Estate Bottled” label and Martini never used it. Instead, both use a definition of their own: “Special Selection,” which means an exceptional wine of such outstanding development that it is set apart from others of the same year. Martini also uses “Private Reserve” to label one of the special wines aged for several years longer than normal.

The last visit in the Napa Valley brought me back full circle from Stony Hill, where this tour began, to another of the smallest and finest of U.S. vineyards. Joe Heitz came into the valley twenty years ago. The U.S. Army stationed him in California during World War II. Anxious to expand his pay, he spent his free time working in a vineyard and became fascinated with wine. At the end of the war, discharged from the Army at twenty-five, he took the graduate course in oenology at the University of California and became a top wine chemist. In 1961, determined to make his own wine, he bought a tiny vineyard in the Napa Valley and gradually expanded it to thirty-two acres with a handsome seventy-five-year-old stone cellar.

I sat on the porch facing the cellar and tasted. We began with a simple white, quite young, 1967 pinot blanc, dry and pure. It had an exquisite aroma, a noble flavor, was delicately juicy and soft, but not yet quite at its peak. It rated a “noble” thirty-six—the best California pinot blanc I had ever tasted. Next, a red, his 1960 “Limited Bottling” cabernet sauvignon, aged three years in wood and six in the bottle. The bouquet overflowed from the glass with an exquisite scent, the first taste was extraordinary, nobly rich and spicy, the liquid felt heavy, almost chewy in the mouth, with a faraway sweetness. It rated a “noble” thirty-nine.

Finally, Heitz provided one of the most dramatic moments of my tour. From the cellar cask he drew out with a long pipette, and ran into my tasting glass, a sample of his 1968 pinot chardonnay. As I swirled my glass, the aroma of the new wine enveloped my face with a small blast of joyous bouquet, like all the wild flowers of the woods concentrated into a single scent. No shadow of doubt about it—this is an exciting and tremendous wine. The taste on the tongue and the feel of it around the mouth are already great and powerful. It rated, still in its infancy, a “noble” forty-one—with the certainty it will be “great” at maturity. (Many California connoisseurs think that 1968 will prove to be the greatest vintage year since Repeal.)

It seemed to be one of the sadder facts of life that these magnificent Heitz wines were not available to connoisseurs outside California. He explained the distribution problems which face all the small fine-wine producers. Heitz would like to sell his wines by mail order to private connoisseurs around the country. Federal law absolutely forbids interstate shipment of alcoholic beverages to a private consumer. Almost every state has a different set of regulations controlling even the wholesale importation, including different laws about labeling, different requirements for packaging and, in some cases, discriminatory taxes. In New York, for example, before a couple of cases of Heitz wines could be shipped to a licensed wholesaler, the Heitz label would have to be registered with the State Liquor Authority and the expense involved might put up the price of each bottle by as much as $2. Heitz thinks the complications are too great. He can sell everything he makes right around San Francisco.

Returning to San Francisco, after drinking all these superbly aged and aging wines in the cellars of the vintners, I was convinced that the major problem for the average buyer of California wines (especially the reds) is that there is a chronic shortage of wines properly aged to full maturity. The vintners do not have the space to hold more than a few “Private Reserve” bottles, but what about the retailers? I spent my last few days in San Francisco talking to some of them. One of the best-known stores is Esquin’s, run like an old fashioned London wine merchant’s, with paneled walls, teak floors, Oriental rugs, but not a salable bottle in sight.

The co-owners, Kenneth Kew and Karl Petrowsky, told me that the cellaring of California wines is made almost uneconomic by the California tax law, which seems to put a penalty on the aging of fine wines. Each year, on March 1, every bottle in storage (and every gallon of wine in cask) is taxed on a percentage of its market value (which works out to be thirty-five percent), multiplied by the tax rate for the year. Thus if a bottle is held for twenty years, it has paid the state in taxes many times its market value. This seems hardly the way to encourage the expansion of the fine-wine section of the industry, which, as in France, is the part that brings the world-wide prestige. The answer, of course, for the knowledgable wine buyer is to lay down his own cellar.

One vintner who does age his bottles in his own cellars is Martin Ray, the enfant terrible of the California wine industry. He refuses to join the Wine Institute, or any other trade association, because he claims that they are dominated by the large producers and are not “working hard enough” toward setting higher legal standards for fine California wines. His own are all vintage, one hundred percent single-grape. I tasted his 1966 pinot chardonnay, which I rated at thirty-eight, and his 1952 pinot noir rated at forty—both easily in the “noble” class.

On my last San Francisco evening, I crossed the Bay Bridge to Berkeley and dined at a bistro called The Pot Luck, co-owned by Henry Rubin, who writes a weekly wine column in the San Francisco Chronicle and maintains what is probably the finest restaurant cellar of California wines in the Bay area. His food could be improved by more imagination and skill on the part of the chef, but his wines are impeccable.

With our fish, we had a white pinot chardonnay from a vineyard which, at least in its original form, no longer exists. Hanzell, in the Sonoma Valley, was named for Hannah Zellerbach, wife of the San Francisco financier and diplomat, James Zellerbach. When he retired, he lavished his capital and time on the vineyard, until he died in 1963.

Now, on the table before me was one of his greatest vintages, his 1960 special pinot chardonnay. Nine years is a dangerously long time for any but the greatest of white wines. This one was still marvelously full and round, powerful, almost oily on the tongue. The aroma still had the characteristic spice of the chardonnay, with a delicate sweetness, a juicy texture and showed no sign of decline. I rated it a “noble” thirty-six, and thought the price of $16 a fair exchange.

With the meat, we ordered what turned out to be the last bottle in the cellar of a truly ancient vintage from Beaulieu, the great Napa vineyard which until recently was run like a French château by its Franco-American owners, the Marquis and Marquise de Pins. (The vineyard was sold to the Heublein Corporation in July and connoisseurs are waiting to see if the quality will be upheld.) The bottle we had was the 1940 “Private Reserve George de Latour” cabernet sauvignon, which by now had been three years in wood cask and twenty-six in the bottle. It was one year older than the great charbono which I had tasted on my first day. How would they compare? The cork was in good condition. The liquid gurgled almost thickly into the glasses. I swirled it. The aroma was exquisite. The first taste was nobly great. The wine was still at its peak. I finally rated it at a “great” forty-three, one point less than the charbono. I considered the $35 price a bargain.

With the dessert, the co-owner of the restaurant, Narsai David, brought each of us a gift of a single glass from a priceless bottle of sacramental wine, made during Prohibition. It was the 1929 Louis M. Martini Muscatel, which had now been in bottle for at least thirty-five years. It was still extraordinary! The sweetness of bouquet and taste was luscious and velvety smooth. There was still the faraway flavor of the muscat grape, with a texture vaguely reminiscent of the lightest and most delicate honey. I rated this extraordinary experience at forty-three, to join the others among the great and noble wines of California.

In the early dawn of next morning, as the sun was burning the mists off the Central Valley and sparking the Flame Tokay vines, we drove east from San Francisco to the small university town of Davis, near Sacramento. The name of Davis is now equal in status to the other major research centers in the science of wine: Bordeaux and Montpellier in France, and Geisenheim in Germany. The man who has made it so is Dr. Harold Berg, Chairman of the Department of Viticulture and Oenology of the University of California. Sitting in his office, surrounded by his acres of experimental vines, I asked if he felt there are differences between California summers and that, therefore, wines should be vintaged from year to year?

“Absolutely, yes.” he said. “There are large variations in California from year to year. Some people, in our industry, seem to be more interested in getting a stable and uniform product than they are in realizing the full potential of the grape. Science can shortcut many a mile for the vintner—but the last hundred yards depend primarily on his common-sense know-how as a farmer and, above all, on the taste buds in his mouth! Remember that wine is one of the most complex substances known to man. In every glass of wine, we know of between two hundred-fifty and three hundred separate organic compounds. There are about a dozen different alcohols, over a dozen amino acids, and the pectins and phenolics number well over fifty. In every glass of red wine, there are between fifteen and eighteen different pigments, all interacting with each other. There are almost a dozen different proteins and sugars, a dozen or so different vitamins, plus about a hundred-fifty different esters and other volatile substances which give wine its aroma and bouquet. Is it any wonder that a truly great wine comes only once in so many years?”

Dr. Berg considered with me some advice that might be given to the average American wine lover, a man who probably knows more about the great French and German products than the best his country has to offer. Four points seem worth noting:

1. California reds show great improvement by being kept even for two or three years and the best will continue developing up to twenty or more years. The whites seldom improve much beyond five years. You must start with the finest vintaged reds, made one hundred percent from a single noble variety of grape. The best in California, particularly from the Napa Valley, is the red cabernet sauvignon, with the pinot noir as second best and the zinfandel third. The wine should, to begin with, be fairly heavy in tannin. Write to the winemaker and ask for his advice about recent vintages that are good to lay down. You can also learn to taste for tannin. Drink a fairly strong cup of tea, without cream or sugar. Note the astringent taste, which puckers your mouth and makes you grimace. This is the taste of tannin, usually called “hardness” in a new wine. It changes, over the years, to a silky richness.

2. Few of the finest California wines are available in liquor stores outside the state. The problems in getting hold of them vary according to the state in which you live. Again, write for advice from the winemaker on the wine in which you are interested. For Napa growers, write c/o the Post Office in St. Helena—or, for the Sonoma Valley, in the town of Sonoma, or for the Livermore Valley, the town of Livermore. Remember that the very small vineyards (Heitz, Stony Hill, etc.) have no distribution outside California. A few the somewhat larger vineyards (Beaulieu, Buena Vista, etc.) do have distribution in some major cities. The largest fine wine producers (Martini, Wente) have national distribution, but for only a trickle of their fine “special reserve” wines. However, when a vineyard has regular wholesale distribution in your area, it means that could legally ship a case two, on special order.

3. Whenever you visit San Francisco, call the vineyard in which you are interested and make an appointment for a visit. The owners are extremely hospitable and willing to discuss which recent wines are best for laying down. You may buy wines at the vineyards in limited quantities and Federal law permits each person in domestic interstate travel to carry, as personal baggage, one gallon of wine (five full, or ten half bottles)

4. After you have laid down your fine red wines, take it easy for a decade or two. Be patient. In time, they will become “noble,” perhaps even “great.”

I stumbled upon this article last year and it took me back down memory lane as I sold and tasted many of these wineries in the 1970's. I viewed Roy making his chicken paprika dish on "Good Morning America " show also in the 1970's and it has been one of my go to recipes ever since. Eric Awes