Electricity in the bottle

Hamel Estate adjusts their farming and winemaking to garner mineral expressions

The original text of an article published in the December 2025/January 2026 issue of The SOMM Journal.

The conscious turn towards mineral profiles

Forever and a day, in the restaurant business, we’ve been teaching our staffs, and sharing with our guests, the differences between New World and Old World wines. Particularly on matters of body and softer fruitiness (New World) vs. crispness, lightness and, last but not least, minerality (Old World).

In 2016, when John Hamel was about to take over the reins as Director of Winegrowing and Winemaking for Hamel Estate—a Sonoma Valley winery founded in 2014 by his parents Pamela and George Hamel—he was not willing to automatically accept the differences between the Old and New. He questioned it.

In a conversation this past summer, Mr. Hamel talked about how Hamel Estate first began making the conscious transition to more place-driven wines, inspired by the Old World:

We grew into what we are doing today a little at a time, starting out with an acre of Cabernet Sauvignon planted on our estate in 2006, adding on another 2 acres soon after that. My dad made the first wine from our own grapes in 2006, and I joined the family business in 2010. Since then our three properties, located in three different parts of Sonoma Valley, have grown to 295 acres, with a total of 91 acres planted mostly to Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Grenache and Sauvignon blanc.

Between 2010 and 2016 we retained a Napa-based consultant. At that time, I’d describe our wines as very Californian. But I was conscious of the fact that the wines I loved to drink most were European. I began to ask, why? What’s missing in California wines? One of the most interesting things about European wines is that many of them are not just about fruit. They are wines of place, often with mineral qualities unique to each place. My question was, how can we achieve a stronger connection to place, and a distinctive minerality, in our own wines? Why not Hamel?

Pedro Parra and innovative polygon farming

The biggest step taken by the Hamel family towards answering those questions began in 2016 with the retaining of Pedro Parra, the internationally renowned consultant. Originally from Chile—taking his Ph.D. focused on terroir and Precision Agriculture at Institut National Agronomique de Paris-Grignon—Parra describes himself as a “wine terroir consultant.” Parra has been doing more than focusing on the geology of vineyards belonging to clients in Burgundy as well as Chile, Argentina, Italy, Armenia, Okanagan Valley and California. If anything, what distinguishes Parra’s work is 1) his studies of the impact of soil on grapevine roots, and 2) the specific sensory repercussions of those findings on resulting wines. To Parra, in fact, unlocking the geology of specific terroirs is less important than getting to the heart of the wines from those terroirs. In short, terroir defined outside the context of wine is useless knowledge.

This approach was exactly what appealed to Hamel, who says:

I think, at first, Pedro was a little skeptical of California, particularly because of our warm Mediterranean climate. But when he first visited our Nuns Canyon Vineyard nine years ago, he immediately recognized how the volcanic soils of this vineyard, on mostly steep 1,198-1,578-ft. elevation slopes, change from pure rock to pure clay and everything in between in all the sub-blocks, usually within a few feet of each other—a shifting of soil content not unlike what you find in Burgundy, which he had a great deal of experience with.

His first order of business was to examine the soils in order to establish a more precise idea of what we had. Parra utilized an electromagnetic scanner to gauge the varying depths of clay in our soils, explaining to us that clay is a key component to building wines with distinctive mouth-feel.

It is interesting to note, in Parra’s many interviews over the years, that he also substitutes the word “electricity” for minerality as a way of expressing sensory reactions to wines on the palate. Although wines are distinguished by aromatic complexities, according to Parra it is the impact of wine in the mouth that is often overlooked. It is the combination of phenolic content and acidity that imparts the qualities most often associated with the minerality distinguishing the best vineyards around the world. This necessitates a focus on farming for mouth-feel.

Nuns Canyon Vineyard—the largest of the Hamel family’s Sonoma Valley properties (58.7 planted acres), located in the Moon Mountain District AVA—has its own interesting history: First founded, by accident (according to legend), back in 1857 as part of Montecillo Vineyard, thus representing one of Northern California’s first “mountain vineyards.”

Walking us through three different soil pits within 30-ft. of each other, Hamel and his full-time viticulturist, Saskia Tingey, pointed out the varying percentages, and layering, of rock, sand, silt, and clay going down 6 feet in each pit. Explained Hamel and Tingey:

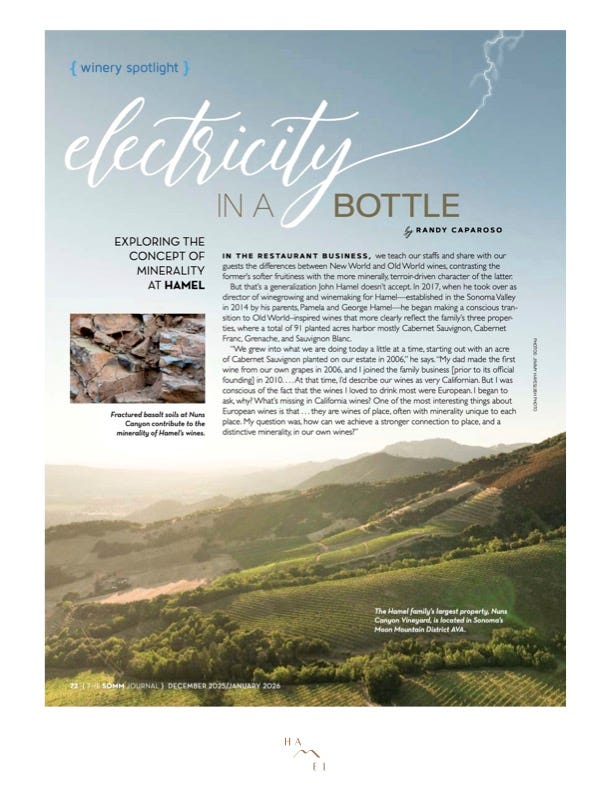

Although our generalized description of the Nuns Canyon soil is “fractured basalt” [i.e., volcanic], the sub-blocks vary, in most cases quite dramatically, all having an impact on the character of our wines. Basalt itself is solidified magma, rich in iron and magnesium. Iron oxidizes from volcanic soil, which can create sensory qualities contributing directly to a minerality sensed by the palate. Our most mineral wines, for instance, come from our rockier sites requiring more vigorous rootstocks. Our more accessible wines come from the sites with higher clay content.

Knowing the clay/rock content made it possible for us to farm and plant with more precision. Based on that, we have divided our sub-blocks into what we call polygons. “Polygon” is a term used in GIS [Geographic Information System] for identifying geographic areas based on their geology. The polygons pinpointed on our vineyard maps are 1/2 to 1 acre in size, and each is farmed, picked and fermented separately.

In the winery, the lots from each polygon are fermented in 3- to 4-ton fermenters, stainless steel as well as oak and concrete; the concrete in 1/2-ton to 4-ton sizes. We also found that the shape or geometry of our tanks is an important factor, impacting the dynamic of the fermentations. Lower surface area at the top minimizes cap size, forcing caps to submerge during fermentation. The objective, however, is not to extract more intensity, but rather the terroir-related sensory qualities unique to each individual polygon, reflecting their soil content.

Adapting winemaking and élevage to the terroir

In the winery, Mr. Hamel and I were joined by his Associate Winemaker Maura Kinsella, a former USA National Team cyclist who also brings a Master’s in Winemaking and Viticulture from University of Bordeaux to the table; joining the Hamel team five years ago following stints at Château Palmer and J.P. Moueix.

Interestingly, though, in the winery Hamel Estate takes fewer cues from the traditions of Bordeaux than those of Southern France because, explains Hamel, “We have not only adapted our winemaking methods to our volcanic terroir, but also to our Mediterranean climate, which is different from what you find in Bordeaux. When you look at winemaking in Mediterranean regions, such as the Rhône and Southern France, you see more usage of larger casks and concrete vats which are generally less oxidative.”

In respect to aging vessels, the French oak casks increasingly employed by Hamel range in size from 8 to 10, 12 and 15 hL (i.e., 800 to 1,500 liters). They also utilize 10 hL Austrian oak casks. This is in contrast to the 225-liter size typifying Bordeaux barrique. Adds Kinsella:

Unlike Bordeaux, there is less need for techniques such as micro-oxygenation in our climate. By moving away from aging in barriques and employing more large casks and concrete, we not only achieve less of the sweet taste of oak—the last thing you want when you want to emphasize balance and minerality—we also get more verticality of richness in our wine. In terms of phenolic content, we’re trying to avoid rustic or astringent tannin. The key is developing a restraint in technique, more gentle extraction, 100% natural yeast fermentation, minimal racking, picking grapes earlier, all the things you can do to achieve a stronger sense of place on a sensory level.

To demonstrate their meticulous approach to farming and winemaking, Hamel and Kinsella pulled out three reds, starting with the 2021 Hamel Sonoma Valley Stratum ($60), a blend of 53% Cabernet Sauvignon with 32% Merlot, 14% Cabernet Franc and 1% Zinfandel from Nuns Canyon Vineyard and the Hamel Family Ranch (Sonoma Valley AVA). The wine was mildly herby, tinged by pencil wood nuance, notably fleshy, earthy, long and savory rather than big, fat or dense. Explained Hamel: “Two things about the Stratum—first, the high percentage of Merlot and Cabernet Franc makes it more accessible, but the second, more telling factor is that it is largely sourced from polygons with more clay content, which adds to that generosity of feel in the mouth. While it still can’t help expressing the mineral character of our vineyards, it is a milder minerality than in our wines coming off our rockier sites.”

That said, the 2021 Hamel Nuns Canyon Cabernet Sauvignon ($160) was a dramatic contrast, even while consisting of 21% Cabernet Franc and 4% Grenache to go along with 75% Cabernet Sauvignon. The wine was a deeper purplish ruby and denser in phenolic content; yet almost wild in a faintly earthy, chaparral-tinged cassis/berry aroma, combining a strong sense of minerals to go along with a svelte, velvety palate-feel. Kinsella commented, “The seven or so micro-polygons going into this wine were selected precisely for their Nuns Canyon typicité. It is deeper, more structured, yet it is the minerality that lifts the wine, adding tension to the palate. 74% was aged in large French and Austrian oak casks, mostly neutral, and just 26% in neutral barrels. I’d say these polygons were about 80% stone and just 20% soil. In these conditions, we have found that even our Cabernet Sauvignon-dominant wines express themselves better without a large percentage of barrique—there is the deep color and tannin that you expect, yet it is very fine grained. I think it is the restrained use of wood that allows the wine’s mineral character to show up, front and center.”

The third bottling—the 2019 Hamel Isthmus Sonoma Valley Red ($90)—was a Cabernet Sauvignon (53%)/Merlot (28%)/Cabernet Franc (18%)/Petit Verdot (1%), mostly from Nuns Canyon Vineyard, 11% from Hamel Family Ranch, aged primarily in neutral oak casks, 22% in French oak barrels. The distinguishing character of this wine was an iron-like note merged with herby and cedary notes, the minerality emerging towards the end of a long and slender, velvety palate-feel. “You can see why,” says Hamel, “we have been moving away from barrique since 2019. It just isn’t necessary to achieve the deep yet balanced, terroir focused qualities intrinsic to the vineyard, which we can now be delineated through our micro-polygon selections in the winery.”

Biodynamic and dry farming

Transition to dry farming has been still another key to achieving Hamel’s terroir objectives. “One thing we learned from Parra,” says Hamel, “is that heavily irrigated vineyards with shallow root systems, less than 2-3-ft. deep, have a more superficial connection to place. To achieve true terroir expression you need deeper root zones, and to get that you need to go to dry farming.”

Therefore, starting in 2017, Hamel began its first trials of dry farmed blocks—a process of reducing irrigation over a period of 4 to 7 years before getting closer to completely “dry.” “Since then,” says Hamel, “we have found a correlation of length of wine on the palate to root depth. Deeper roots also correlate with higher phenolic content in the structure of wines. More superficial roots result in more superficial depth in wines. Going beyond that, the deeper the roots, the more minerality we seem to achieve in our wines.”

Although all the Hamel properties are CCOF certified organic, it is their certified Biodynamic practices that have been even more of a natural extension of Hamel’s farming and winemaking practices. Hamel adds, “If the soul of the wine comes from the soil, then we need to do everything possible to enhance the health of the soil and vines. As a holistic approach, it’s Biodynamic farming that gives us the best chance of achieving our goals, which is wines with not just depth, elegance and structure, but also a mineral character unique to Hamel Estate.”

Great to read that Hamel stopped to think about new vs old world methods of grape growing and wine making. Apparently, in their case it's working very well. Would only hope more California wineries, especially on the hillside consider more old world.